Bringing America’s waters back to life

Three chapters in the decades-long struggle for clean water

A river runs red

Few places better embody the adage that America has more problems than we should tolerate than Ohio’s Cuyahoga River.

On June 22, 1969, the river caught fire. Witnesses reported the flames reached as high as five stories, fueled by a discharge of volatile petroleum byproducts amid a layer of oily wastes that sometimes bubbled like a boiling stew.

In July, TIME magazine featured the Cuyahoga fire on its cover. Other media, as well as advocates such as Ralph Nader, carried the story forward and the river on fire became a rallying cry for the environmental movement that would soon lead to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972.

The price of progress

Yet 1969 was not the first time the Cuyahoga caught fire. Not even the second. It was the 10th, at least, dating back to 1868.

For a century, the river had been treated like a sewer by the oil, steel and other factories along its banks. For most of that time, for most people, the river’s oil slicks (on which sometimes floated bloated dead rats) and foul smell, along with the general rule that a fall into the river required an immediate trip to the hospital, were small prices to pay. As one author put it, “this level of environmental degradation was accepted as a sign of success.”

But not anymore. Americans no longer tolerate our rivers catching on fire. Through dozens of campaigns, people have demanded action to bring our rivers, along with our lakes streams, wetlands, bays, estuaries and beaches, back to life. In 2022, as America marks the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, we look back at three of The Public Interest Network's clean water campaigns, including efforts to crack down on illegal pollution, shield rivers from development, and restore protections to small streams and wetlands.

Video credit: Pronghorn Productions via Shutterstock

A bombshell report

For two years (1984-1986), NJPIRG staff gathered, examined and re-examined reams of government records: water pollution discharge permits, discharge monitoring reports, sewage treatment plant records, and government action files.

The findings were damning: 3,009 pollution permit violations by industrial and sewage treatment plants; only 53 violations (2%) prompting any government response (typically a phone call or a letter); and only two violations resulting in fines. The report summarizing the findings, entitled “Polluters’ Playground” and released on Feb. 19, 1988, concluded:

A clear pattern of industry law-breaking and the laissez-faire approach of government agencies has created a polluters’ playground in which chronic and substantial pollution violations are routine.

The report was shocking, but not surprising, to many at NJPIRG.

Wading through troubled waters

For decades, NJPIRG staff, along with most New Jerseyans, were well aware that oil refineries and chemical plants had dumped their wastes into New Jersey’s rivers and streams virtually unchecked – making fishing and swimming in many waterways not just unsafe, but unthinkable.

Beginning in 1974, teams of NJPIRG volunteer “streamwalkers” pulled out hip waders and walked or canoed through waterways, looking for and too often finding evidence of illegal pollution.

With help from NJPIRG’s professional staff, the streamwalkers contacted state officials with the evidence they uncovered and set up a 24-hour pollution hotline. In 1983, the organization initiated a series of lawsuits against violators, citing as evidence the offenders’ own discharge reports. Yet state and federal officials still refused to crack down. NJPIRG was plugging a broken dam with cotton balls.

According to former NJPIRG director and general counsel Ed Lloyd, “we were looking for systemic change – mandatory minimum fines that would be required of all companies that violated their discharge permits.”

Enter the New Jersey Clean Water Enforcement Act.

Needles on the beach

In 1988, it was far from certain that New Jersey lawmakers would pass the Clean Water Enforcement Act, a bill that would set the tough, mandatory fines that Ed Lloyd had called for.

Four things gave the bill the momentum it sorely needed:

Not only did NJPIRG’s “Polluters’ Playground” report earn widespread attention in the state, but the group’s staff produced a series of mini-reports detailing the problems in the districts of key legislators.

NJPIRG built a coalition of more than 100 organizations, including not just the usual environmentalists but also outdoors enthusiasts, religious groups and Jersey Shore business owners.

To help garner even more attention for the campaign, staff constructed an 18-foot prop fish (called Wanda). Wanda joined NJPIRG and our allies at most campaign events.

In the summer of 1988, garbage, medical waste and even used syringes washed up on the Jersey Shore, dramatically illustrating the need to crack down on water pollution.

On May 24, 1990, Gov. Jim Florio signed the clean water enforcement act into law after both houses of the state legislature unanimously passed it. Within a decade, New Jersey rose from near the bottom to near the top for compliance with Clean Water Act permits. And California passed a similar CALPIRG-backed law in 1999.

Photo: staff

NJPIRG streamwalkers protest illegal discharge at Morses Creek in 1986. By staff

NJPIRG Legal Counsel Ed Lloyd files lawsuit against water polluter in 1983. By staff

NJPIRG Advocate Rob Stuart and Gov. Jim Florio speak in support of clean water alongside Wanda the Fish prop, 1990. By staff.

A development boom, unsafe rivers

It’s the 1990s and development in Massachusetts is booming, outpacing population growth by a rate of 6 to 1.

Yet more development often means more pesticides, oil and other pollution running off into the Bay State’s 9,000 miles of rivers. A 1996 MASSPIRG study finds 68% of the state’s rivers unsafe for fishing or swimming. The national average is only 38%.

MASSPIRG joins a coalition of canoeists and fishermen, throwing our weight behind the Rivers Protections Act, which promises to shield rivers with 200-foot (or 25-foot in urban areas) “buffer zones” -- corridors in which development is barred, giving riverside vegetation a chance to filter out contaminants before they run off into the water.

Introduced seven years earlier by Sen. Robert Durand, by 1996 the Senate has passed the bill four times. In the House, however, the real estate lobby’s opposition has proven stronger. Each time the Senate passed the bill, the House let it die.

As the 1996 legislative session begins, changing the bill’s fate in the House will require a combination of public support and strategic advocacy.

Two weeks notice

The Rivers Bill coalition overcomes a major hurdle when the powerful House Ways & Means Committee approves the bill -- on July 19, only two weeks before the end of the session.

The tight timeline isn’t the only problem.

MASSPIRG’s Rob Sargent and Paul Burns are among those who discover a monkey wrench: The bill headed toward the House floor carries an amendment that would shield companies from responsibility for hundreds of hazardous waste dumps. Among the companies that would benefit: Generic Electric, owners of a Pittsfield plant that had contaminated the Housatonic River with dangerous PCBs.

On July 22, MASSPIRG and our allies deliver a clear message to lawmakers: No polluter-friendly amendments. Pass the bill in its original form.

The next day, with the clock winding down on the legislative session, Paul organizes 65 volunteer phone bankers to rally activists around the state. Thousands of calls and letters flood lawmakers’ offices.

Crunch time for the Rivers Bill

On July 25, with the session ending in just six days, the House approves the Rivers Bill -- but with a watered-down yet still polluter-friendly amendment, crafted to protect only General Electric.

The bill heads to a conference committee. On July 28, in a meeting with Rob, Paul and another environmental advocate, Sen. Durand agrees to hold firm on his original bill.

The next day, Rob helps sleuth out that the polluter-friendly amendment originated in the governor’s office of business development. After Rob tips off reporters, the story runs in the Boston Globe.

On July 30, Rob and Paul, our twin river stewards, show up early at the State House, urging members of the joint House-Senate conference committee to approve a strong Rivers Bill.

Well after midnight, in the early hours of July 31, Rep. Barbara Gray, one of our top allies on the Rivers Bill, emerges from behind the closed doors of the conference committee.

“Did we win?” Paul asks. Rep. Gray responds, “How do I look?” “You look tired,” Paul says. “But I feel great!” she shouts back.

The conference committee had agreed to pass a strong Rivers Bill, providing new protection to 9,000 miles of the state’s rivers. Peter Schilling, of Trout Unlimited, praises Rob and Paul for their advocacy, saying “it was the attitude and spirit they both carried, and vocalized, which helped turn the tide in getting the Rivers Bill passed.”

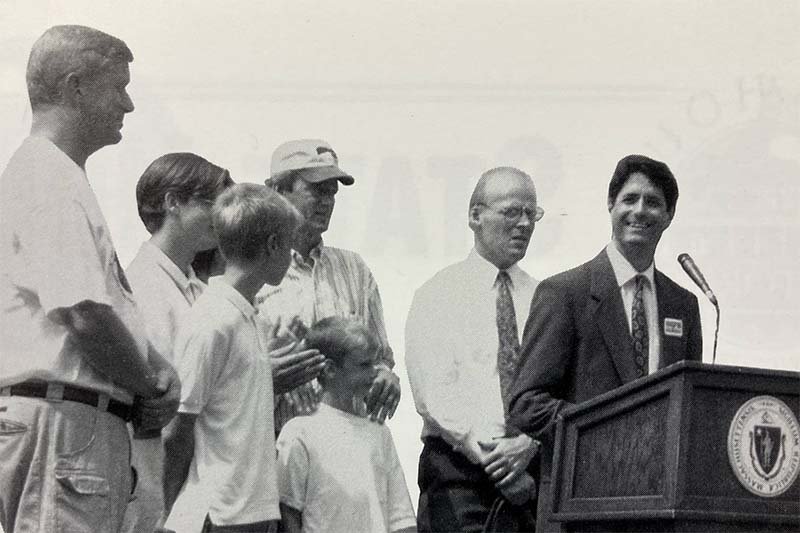

On August 7, Paul stands at the podium and speaks before Gov. Bill Weld signs the bill into law. The governor and Sen. Durand take a celebratory leap into the Charles River, which would soon be called the cleanest urban river in the country.

Photo credit: Pixabay.com

MASSPIRG’s Rob Sargent (left) talks with Sen. Robert Durand about the Rivers Protection Act. By staff

MASSPIRG Attorney Paul Burns spoke on behalf of the environmental community at the signing of the Rivers Bill on August 7, 1996. Next to Paul are Gov. Bill Weld, Sen. Bob Durand and his three sons, and Sen. Warren Tolman. By staff

Gov. Bill Weld and Sen. Robert Durand leap into the Charles River at the event marking the passage of the Rivers Bill. AP Photo/Gail Oskin Click the image to watch the epic leap into the Charles.

Which waters deserve to be clean?

The most consequential debate over clean water in 21st century America has hinged on the definition of one word: navigable.

On June 19, 2006, a rare 4-1-4 Supreme Court decision muddies the meaning of the 1972 federal Clean Water Act, the primary law governing protection of the “waters of the United States.”

The case was brought by John Rapanos, a Michigan landowner who wanted to pave over wetlands to build a strip mall. When officials told Rapanos he needed a permit under the Clean Water Act, he sued. The case reached the Supreme Court in 2006, and Justice Scalia wrote an opinion that would have drastically scaled back the wetlands and other waterways protected by the Act. Fortunately, most courts since then have been guided by Justice Kennedy's concurring opinion in the case, which said that waterways are protected under the Act if they have a “significant nexus” to navigable waters. While far better than Scalia’s drastic alternative, the significant nexus test left 20 million acres of wetlands and half of our nation’s streams in legal limbo.

That put downstream larger rivers and lakes — as well as the drinking water for 117 million people — at risk from pollution.

Restoring these protections would become the biggest clean water battle of the next decade and a half.

Winning the Clean Water Rule

After the 2006 ruling, Environment America and other clean water allies urged Congress to restore protections to the nation’s streams and wetlands. However, the opposition of developers, oil and chemical companies and agribusiness stymied action on the issue.

Upon the election of President Obama, Environment America urged his administration to use its existing authority to clarify that -- given the intent of Congress for the Clean Water Act to regulate the “waters of the United States” and the scientifically significant nexus between streams that feed rivers, as well as the wetlands that filter pollutants from them -- the law must protect all the nation’s surface waters.

We found support within the administration, but such an action would require strong public and political cover as well as scientific and legal backing.

Under the leadership of Margie Alt and John Rumpler, Environment America launched a campaign to win a new Clean Water Rule. John and his team, with assistance from Frontier Group, researched and released a series of reports on water pollution problems, including the impact of clean water protections on 15 major waterways.

Environment America staff and members also held meetings with more than 50 congressional offices, building a firewall against any attempt on Capitol Hill to block or rescind administrative action on the issue.

And across the country, the directors of our state environmental groups, organizers and canvassers helped enlist more than 1,000 leaders (including business owners, elected officials, farmers and health professionals) and 1 million citizens to show their support for the Clean Water Rule.

On May 28, 2015, President Obama announced his approval of the new rule. The New York Times quoted Margie Alt saying “today’s action is the biggest victory for clean water in a decade.”

Then came the Trump administration.

Bridging troubled waters

On Day 1 in office, President Trump vowed to repeal the Clean Water Rule. In 2020, he succeeded — to a point.

On January 23, the administration announced it was replacing the Clean Water Rule with a plan we called the “Dirty Water Rule,” categorically stripping clean water protections from thousands of streams and wetlands -- including many of those we helped protect in 2015.

Yet when President Joe Biden took office in 2021, our network’s supporters sent thousands of messages urging his EPA to restore the Clean Water Rule. On June 9, EPA Administrator Michael Regan signaled his intention to do just that.

It’s been a long, bumpy road. But federal protections for the waters of the United States — including half of our wetlands, 2 million miles of streams, and the drinking water of 1 in 3 Americans — are coming back. And America’s waters are — slowly — coming back to life.

Photo credit: Pixabay.com

Environment America’s Anna Aurilio joins Sen. Ben Cardin (Md.), Clean Water Action and other allies to present more than 700,000 petitions from Americans to the EPA’s Ken Kopocis in support of clean water protections on Oct 22, 2014. Photo by Elena Nagornykh

Environment America’s Margie Alt at the Clean Water Rule signing on May 27, 2015. Photo by Sean Kennedy

Environment New Jersey activists at a river paddling event in support of water quality protections in 2015. By Nicholas Thomas